Gasoline Price Cycles in Germany

Gas stations in Germany are required by law to send their prices to a central database, maintained by the German Cartel Office. Regular people like you and me can apply to access the data for the purpose of building websites or apps to help consumers find cheap gas stations.

A while ago a friend and I did just that and built https://mcsprit.de.

There are many of those services; the Cartel Office lists them on their website.

While working with the data, I found the following:

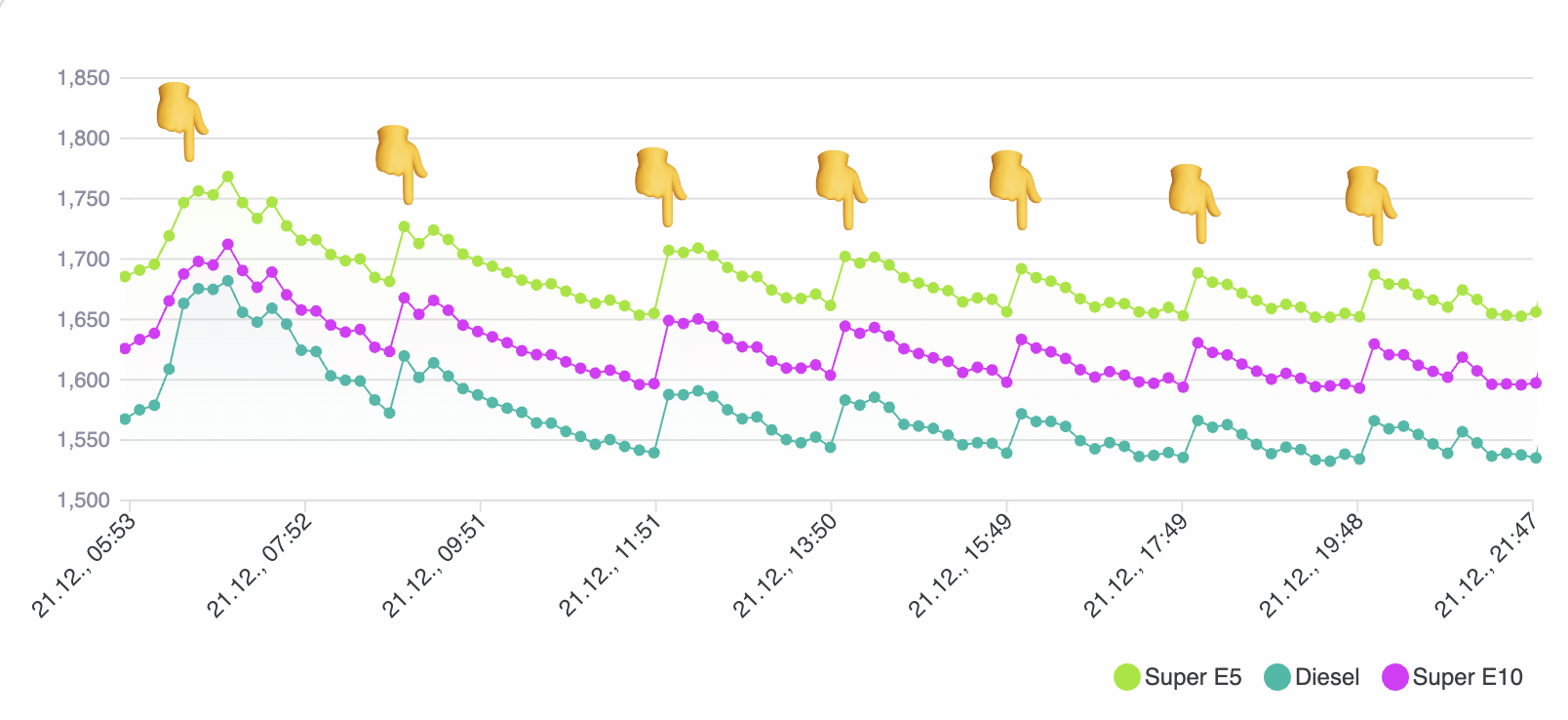

A chart of average prices in euros for Diesel, Super E5 and Super E10 of all 15075 gas stations in Germany from 2025-12-21 5:53 to 2025-12-21 21:47 at 10 minute intervals.

There are sudden increases followed by gradual decreases in the prices of all three fuel types, and I wondered why.

Demand

My initial thought was: The first spike is caused by early commuters, starting to work at 7:00, then a second wave starting at 8:00, and so on; elevated demand causing prices to rise.

But I would expect a more wavy pattern then, not these sudden jumps. Also, there are too many spikes. The amount of cars on the road does not really spike, I thought.

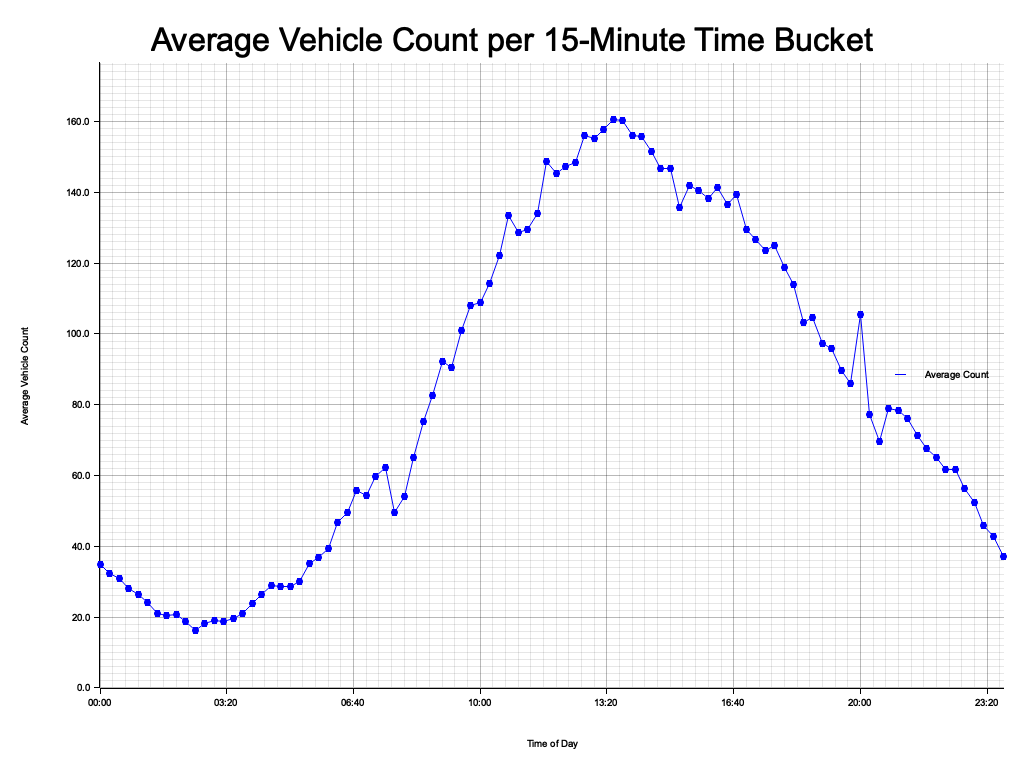

To check that, I downloaded a dataset from Hamburg's Transparency Portal. Hamburg publishes data of infrared traffic sensors with a resolution of 15 minutes. Here is the average amount of cars passing a sensor per 15 minutes from all 52 active sensors plotted for 2025-12-21:

I am using the volume of cars on the road as a proxy for demand at gas stations here. The curve does not show many sudden jumps, with an exception at 20:00. To be fair, this is car volume in Hamburg only, not nationwide. But fuel prices in Hamburg alone show the same pattern as the nationwide average. This suggests that, at least in Hamburg, the price patterns are not correlated with demand.

Supply

Gas stations have to buy their fuel at some price, which I thought could vary a lot over the day. The German Cartel Office says:

After the oil has been processed in refineries, the oil products are sold on wholesale markets mainly on the basis of long-term supply contracts (term contracts); the volumes traded on the spot market are much smaller. Press Release on Sector Inquiry on Refineries

Gas stations mostly buy fuel based on long-term contracts. And those long-term contracts are pretty long:

In detail, the inquiry found that well over 50 per cent of all volumes traded at the wholesale level, irrespective of the product traded, are based on term contracts, which typically have a term of one year. Sector inquiry 2025, Cartel Office

The contracts might last a year, but the price gas stations pay for fuel...

...is based on the price assessment provided at the contractually agreed point in time (e.g. the time of supply) or on the average prices over a specified period (usually the month or week of supply) Sector inquiry 2025, Cartel Office

So prices change on a monthly or weekly bases. If the price assessment is based on delivery, then the price changes as often as the gas station gets deliveries. Some stations get multiple deliveries per day, but I doubt they are as frequent or synchronized across stations as the price changes in the chart.

From what I can tell, supply prices are unlikely to be the cause of the price pattern either.

Price cycles

If supply and demand are not correlated with the price pattern, then what is?

The best theory I've found to explain this particular pattern is described in the Competitive price cycles paper. They specifically look at diesel prices in Germany in 2019. It's a derivative of the well-known Edgeworth price cycle theory. Bottom line, very broadly, is this:

Some customers are price sensitive and buy at stations with lower prices, others are more brandloyal and shop at their preferred station, even if prices are a little higher. From here it goes like this:

- To get more nonloyal customers, ALL stations lower prices

- Prices lower further over time, with every station trying to undercut the others

- At some point prices have to rise, otherwise stations make no profit

- Stations with loyal customers raise prices first and drastically, but not so much that they lose loyal customers

- Other stations follow quickly, as their current prices are way too low compared to competitors

- Repeat

The key points here, I think, are that bigger brands with more loyal customers initiate the price increases. There is no point in ramping up slowly, because most other stations will still be cheaper anyway. So they do it quickly and drastically. And they can do so because they can be somewhat sure customers loyal to them will stay.

Other gas stations then follow very quickly, leaving little time for consumers to benefit from the lowest prices. This raises the question...

Where do gas stations get their competitor's prices from?

The theory above assumes that gas stations know their competitors' prices in (almost) real time.

Consumers are using the fuel price apps to find cheap stations. It would be naive to think that gas station owners don't use these services as well. In fact, the central database maintained by the Cartel Office is, in my opinion, the only practical way to get near-real-time prices of competitors.

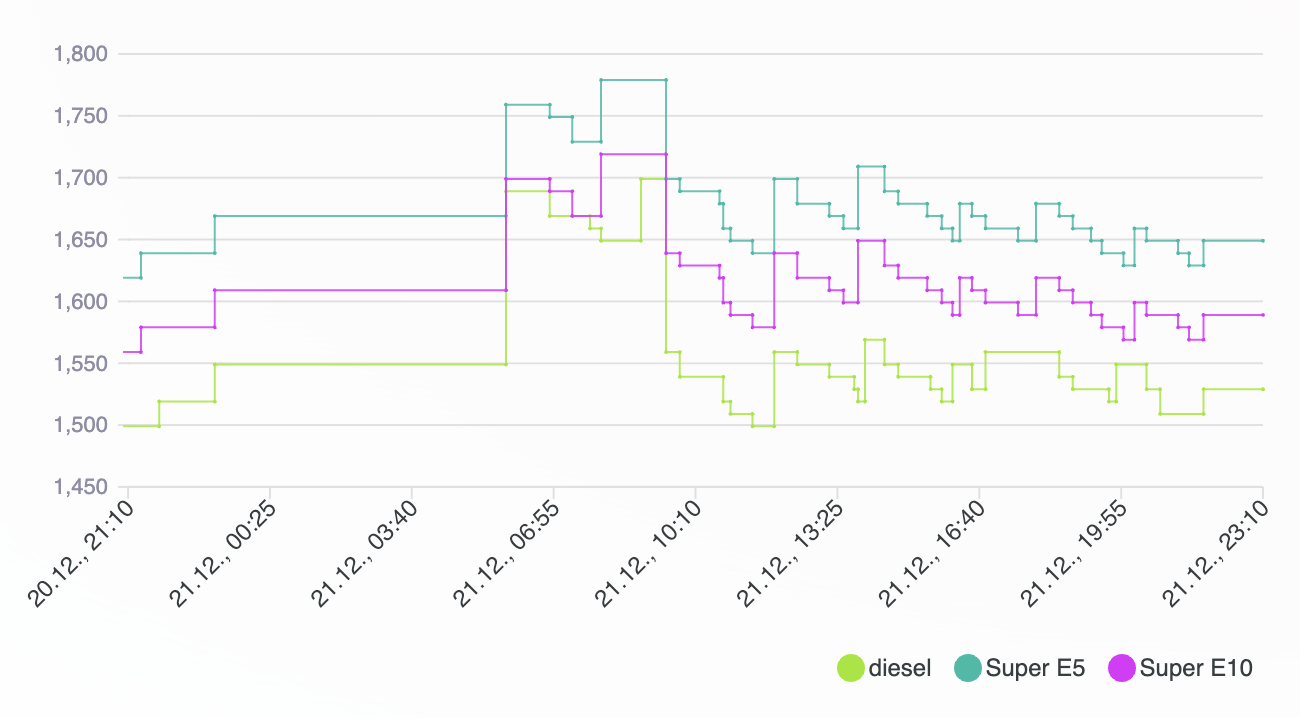

Earlier, we looked at the average prices across all gas stations in Germany, but the pattern is visible at individual stations as well:

This GIF shows the prices of two individual stations on the same day (one frame per station). The stations are on the same road, about 5 km apart. One is a JET station, the other is an OIL! station. As far as I know, JET and OIL! are not part of the same company. There is also no clear line of sight between the two stations. They can't see each other's price boards. Yet, their prices are pretty much in sync down to just a couple of minutes.

This is not an isolated case. See for yourself by picking pairs of stations in one of the price apps listed by the Cartel Office.

Are gas stations allowed to use the data?

Disclaimer: I'm not a lawyer.

To access the real-time data, you have to apply at the Cartel Office. You have to use your access to build some kind of publicly available price app or website for consumers.

The Cartel Office can revoke access to the data for price apps if they find that data is provided to, say, mineral oil companies. Aside from that, there seems to be no kind of punishment for either services providing the data to mineral oil companies or mineral oil companies using the data.

So mineral oil companies cannot directly access the data nor apply for access themselves. But they can get the data from the same price apps consumers are using. Since the apps are required to be public, there is little to prevent gas stations from using them to get competitor prices.

Note that applying for access to the data is completely free, yet a bit of a bureaucratic hassle.

To be clear, I strongly believe the Cartel Office has this database for the sake of consumers. Station owners accessing the data is just inevitable.

Are consumers getting more transparency?

Thanks to the central database, prices are very transparent. But by now they change so frequently that it is questionable if consumers really benefit. How useful is it to know the price at a gas station if it might change again before you get there?

While prices were changed around four to five times a day in 2014, the number of price changes already reached an average of 18 times a day in early 2024 and is still on the rise. Press Release on Sector Inquiry on Refineries

What should consumers do?

Price differences between stations at any given moment are still relevant and differ by several cents per liter. For example, stations near highways tend to be much more expensive.

Using an app to find a station that's cheaper right now is still useful. But actually getting the exact price an app shows you is unlikely when refueling during these price cycles. More so when you have to drive a while to get to the gas station.

If you're feeling lucky, you can try to time your refueling just before a price spike. If you can wait, refuel later in the day. And if you have time and want to play safe, find a cheap station at night. Most stations are pretty expensive at night, but if you find a cheap one, it's also likely to stay cheap for a while:

The chart shows fuel prices of one station for just over 24 hours. Note that there are no changes at all between 2025-12-20 22:00 and 2025-12-21 05:00.

Regulation

With a resolution passed on 21 November 2025, the German Bundesrat (Federal Council) calls on the federal government to examine how petrol prices can be made more transparent for consumers, specifically by limiting the number of price increases per day.

It is not safe to say that limits on price changes would benefit customers after all. Stations may set prices a bit higher by default to account for less frequent opportunities to increase them later. But customers would at least have a more stable price environment to make decisions in.

Austria implemented such limits, allowing for just one price increase per day, exactly at 12:00. Price decreases are allowed at any time. As a result, the best time to refuel in Austria is just before 12:00, while prices after that are probably higher than they would be without the regulation.

Conclusion

Real-time fuel price data can be used by consumers and gas stations to their advantage. The situation for customers is not ideal as prices change often and in sync with other stations. The price you see in an app might not be the price you pay when you get there. And since most stations' prices rise and fall together, looking out for alternative stations is less useful, since all are either up or down at the same time.

Putting regulation in place to limit price changes could help, but designing such regulation is not trivial.

Opinion

Since this is, after all, my personal blog, here is my very personal opinion on the matter:

Introducing the central database for fuel prices was a good idea. I support gathering non-personal data that was very public anyway, just not centralized and therefore hardly useful.

Aforementioned price cycles are a known phenomenon in economics and have been for many decades. Economics is not my strong suit, I still think this outcome could have been predicted to some extent. Politics, also not my strong suit, could have put limits on price changes into the same piece of legislation that introduced the requirement to report prices to the Cartel Office. Arguing for this would have been reasonable back then, when price changes were way less frequent anyway.

The second-best time to push for limiting price changes would be now. We got the data, we see the effects. Prices are transparent, yet of little use to customers if they are altered within minutes. It might be unclear how to exactly design the limits, but other countries have done it, let's learn from them. The current situation is clearly not ideal for consumers.